BOSTON — Madeline Szoo grew up listening to her grandmother talk of being laughed at when she spoke of going to college and becoming an accountant.

"'No one will trust a woman with their money,'" relatives and friends would scoff.

When Szoo excelled at math in high school, she got her share of ridicule, too — though it was slightly more subtle. "I was told a lot, 'You're smart for a girl,' " she said. "I knew other girls in my classes who weren't able to move past that."

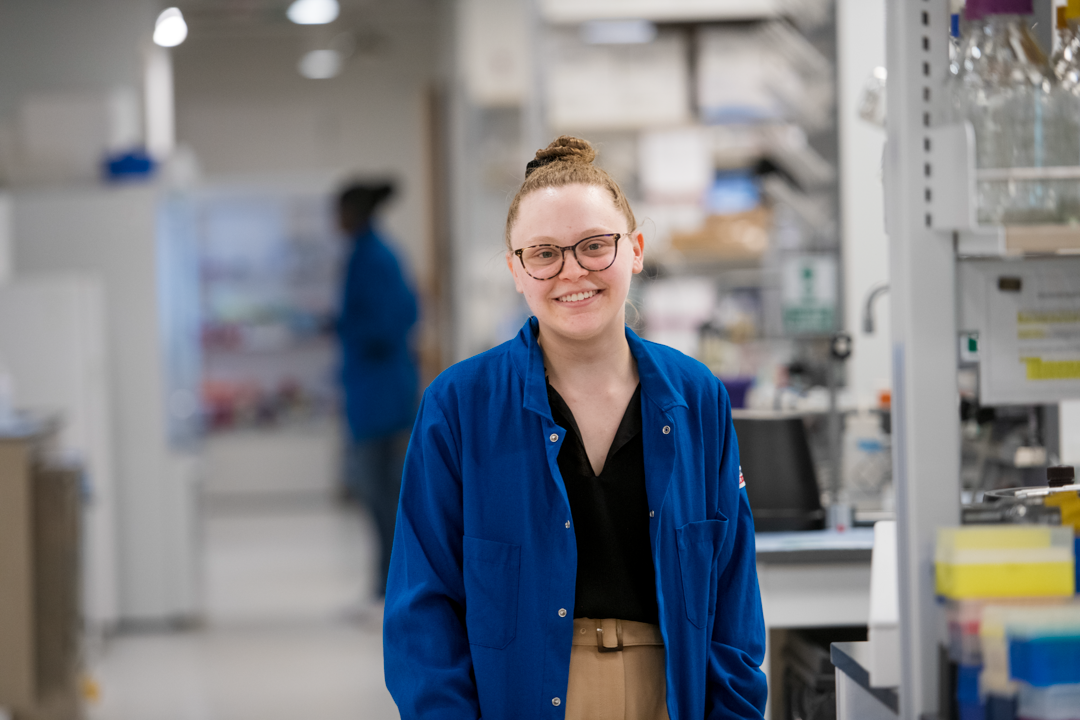

But Szoo tells The Hechinger Report that she had no doubt she'd go to college, with plans to get a Ph.D. and become a mentor to other women as they break through glass ceilings in fields such as chemical engineering and biochemistry, which she now studies as a fourth-year student at Boston's Northeastern University.

Szoo is part of a long-running rise in the number of women getting higher educations, even as the number of men has been declining — a trend beginning to hit even male-dominated fields such as engineering and business. The number of college-educated women in the workforce has now overtaken the number of college-educated men, according to the Pew Research Center.

But while this would seem to have significant potential implications for society and the economy — since college graduates make more money over their lifetimes than people who haven't finished college — other obstacles have stubbornly prevented women from closing leadership and earnings gaps.

Women still earn 82 cents, on average, for every dollar earned by men, Pew reports — a figure nearly unchanged since 2002. And, after steadily increasing for more than a decade, the proportion of top managers of companies who are women declined last year, to less than 12 percent, the credit ratings and research company S&P Global says.

"I think we're getting there, but it's slow," said Szoo, (pictured below) in a conference room of a gleaming new engineering and robotics building on Northeastern's campus.

That slow progress comes despite the fact that women now significantly outnumber men in college. The proportion of college students who are women is closing in on a record 60 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Women who go to college are also 7 percentage points more likely than men to graduate, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center reports.

While engineering is one college discipline in which men continue to outnumber women, Northeastern has since 2022 even been admitting slightly more female than male first-year engineering students.

Still, said Elizabeth Mynatt, dean of Northeastern's Khoury College of Computer Sciences, "In no way have we declared victory."

For one thing, many of the rest of the degrees that women earn are disproportionately in lower-paying fields such as social work (89 percent women) and teaching (83 percent women); women still comprise fewer than a quarter of engineering majors nationwide, and fewer than half of business majors — fields that can lead to higher-paying jobs.

"Even as we see some shifts and changes, disproportionate numbers of men are pursuing pathways through higher education that tend to lead to higher earnings," said Ruth Watkins, president of postsecondary education at the Strada Education Foundation.

As in Szoo's case, the disparity begins in high school, where classes in subjects such as math, engineering and computer science "are still pretty gendered," said Mynatt. "And if you don't know you want to be a computer scientist as a sophomore in high school, you're going to have a hard time getting into that program."

As early as middle school, more than twice as many boys as girls say they plan to work in science or engineering-related jobs, one study by researchers at Harvard found.

Another Northeastern engineering major, Carly Tamer, said she wasn't outright discouraged pursuing that subject in high school, "but there wasn't strong encouragement."

Other factors, beginning in college, perpetuate the disparities. Even with enrollment now female-dominated, women make up only a little more than a third of full professors and a third of college presidents, according to the American Association of University Women and American Council on Education, respectively.

Women who start in engineering in college are more likely than men to change their majors. Nearly half of the women who originally planned to major in science or engineering switch to something else, compared to fewer than a third of men.

"It was awful," Mynatt said of her own experience as an engineering student in the 1980s, before she changed her major to computer science. "It was very male dominated. It had such a weed-out culture. I didn't like the culture. It was about intellectual superiority and competing with the person next to you."

That weed-out approach can be particularly tough on high achievers used to positive reinforcement, Tamer noted. "It can scare people away." She said having more women around her, as she does in Northeastern's engineering program, has proven more supportive.

Even there, Szoo said, she thinks projects submitted by men are sometimes taken more seriously than those turned in by women.

Once they move from college to the workforce, women still overwhelmingly bear family caregiving responsibilities that can interrupt their careers, said Joseph Fuller, professor of management practice at Harvard. Sixty-one percent of caregiving falls to women, according to the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP, formerly the American Association of Retired Persons.

"The career path associated with decision-making jobs and highly paid jobs, their design logic and even their language is still firmly rooted in a 1960s paradigm," he said. "If you go to a big global company, the path to the C-suite anticipates one or two international assignments, four or five relocations, very demanding work hours. There's nothing that prevents a man or a woman from making those commitments, but if you're the principal caregiver, those burdens still disproportionately fall on women."

Caregiving responsibilities also come at points in workers' careers when they are developing networks and relationships, Fuller said.

A study by the consulting firm McKinsey & Company and the women's advocacy organization Lean In finds that even as they are more likely than men to finish college, women in corporate roles are less likely to be promoted from entry-level jobs to management positions. Eighty-seven women advanced in their companies, it found, for every 100 men.

Researchers call this obstacle more of a "broken rung" than a glass ceiling.

It's not that women don't want to be promoted; nine in 10 say they aspire to move up, and three in four want to become senior managers, the McKinsey & Company study found.

Yet 75 percent of senior management jobs are held by men, S&P Global reports.

"The fundamental bias and the systemic issues in corporate America that are fueling women's underrepresentation — they haven't changed," said Caroline Fairchild, Lean In's vice president of education.

Among the many reasons for this, Fairchild said, is that men are more likely to find professional mentors and role models.

There has been progress of another kind, however, Mynatt said: Those many college-educated women entering the workforce, especially in male-dominated industries, are changing perspectives.

She told the story of a female computer scientist who used algorithms to identify the kinds of wrist injuries that show up on X-rays after accidents versus the kind that might be the result of domestic violence.

"The technology was there. The issue was who was motivated to ask the question. What matters is that the women bring the problem to the team," said Mynatt. "When you bring in diverse voices, it shifts things culturally across the board."

Another change: The more women there are in senior leadership positions, the less gender-stereotyped language their companies use, researchers at Duke, Stanford and Columbia universities and the University of Chicago found.

At Northeastern, women engineering and computer science students have won awards for projects such as an app on which people can anonymously report harassment, catcalling and sexual assault.

As for Szoo, she hopes to use her chemical engineering degree to help treat cancer.

After her plans for an accounting degree were thwarted, Szoo's grandmother became a middle school teacher, then started her own business — for which she did her own accounting.

"We're definitely the type of people who if you say we can't do it," Szoo said, "we will prove you wrong."

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.